Sardinia is an island famed for its unearthly beauty. Sardinia is second only to Sicily in its size among the Mediterranean islands. Like Sicily, Sardinia attracted numerous waves of invaders: Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, the Italian city-states of Pisa and Genoa, and the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon—all succeeded one another in dominating the island. The Northern Italians came last, with Garibaldi himself falling in love with the island. He chose to live the last years of his life in Carpera, Sardinia.

Renowned for its great beaches and luxury resorts overflowing with tourists from all over the world, Sardinia tightly guards its ancient secrets, but for the persistent Jewish history pilgrims, these secrets reveal themselves, one story at a time.

The beginning of the Sardinian Jewish story

The first facts about the Jews in Sardinia came to us from Flavius Josephus, born Joseph ben Matityahu. This first-century Roman-Jewish scholar recorded in his study Antiquities that in 19 AD, four thousand Jews were deported to Sardinia from Rome by the Emperor Tiberius. Flavius noted with sadness that the emperor “punished so many” for the “crimes of the few.” These “few” were four crooks who persuaded a senator’s wife, a convert to Judaism, to invest large sums of money in a non-existent synagogue, which these liars claimed to represent. The Emperor hoped that the Jews would perish in Sardinia. Instead, the numerous descendants of the exiles built a prosperous life for themselves and became indispensable for the island’s rulers in trade, finance, money-lending, crafts, and medicine. In the city of Alghero during the Aragonese (Spanish) rule, the Jews were exempt from paying customs duties and were even allowed to display the royal coat of arms on the synagogue as a sign of their importance to the Crown. While the island’s largest Jewish community was in Alghero, thriving communities existed in a number of other Sardinian cities, like Sinai, Nora, and Cagliari, the island’s capital.

As recorded inJewish Encyclopedia, archeologists note that Sardinia is one of the few places in Italy with catacombs containing Jewish inscriptions written in “ebraico-latino” or Hebrew with Latin. Even today, the Sardinian language contains what linguists call “a hint at a Jewish presence,” a few words that might represent an influential Jewish presence. For example, the word caputannifor September is a literal translation of Rosh Hashanah as “head of the year.”

Walking through Jewish Cagliari

In Cagliari, our first stop was the Il Castello district of the island’s capital. Named after the medieval hilltop castle, Il Castelo or Su Castedu in Sardinian is one of the most photographed iconic images of Cagliari. Built first by the Pizans and then by the Aragonese, this city within the city with its gothic and baroque palazzi of Italian and Spanish aristocrats was also a home to a prosperous Jewish community. Even today, 500 years after the expulsion and total annihilation of the Sardinian Jewry, the area of Il Castelo called Ghetto degli Ebrei is one of the most attractive places in Sardinia for Jewish history pilgrims. The former Jewish Ghetto is located north of the medieval Torre del’Elefante, built by the Pizans as a defensive structure against the Aragonese. In the late 1400s, all Cagliari Jews were forced to move into this small area located between the streets Via Santa Croce and Via Stretta and to wear special identifying clothes. In the years preceding the infamous Edict of Expulsion, the ominous influence of the “Most Catholic Monarchs,” Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, was painfully felt in Cagliari.

Walking though the winding narrow streets of Ghetto degli Ebrei, we found the Church of Santa Croce. During this trip we learned that in both Sicily and Sardinia, the churches’ names like St. Giovanni (John the Baptist) or Santa Croce (Holy Cross) served often as an indication that they were built on the foundation of a demolished or reconsecrated synagogue. As a 2006 restoration confirmed, Cagliari Santa Croce was indeed built using the main synagogue’s structure. Only the neighborhood’s name “Ghetto degli Ebrei” points at the historical Jewish presence, while the former military barracks built on the foundation of the old Jewish houses display the sign “Centro Comunale d’Arte e Cultura il Ghetto.” But this is an exhibition place now, with no connection to Sardinian Jewish history.

Garbage dump on the site of a Jewish cemetery

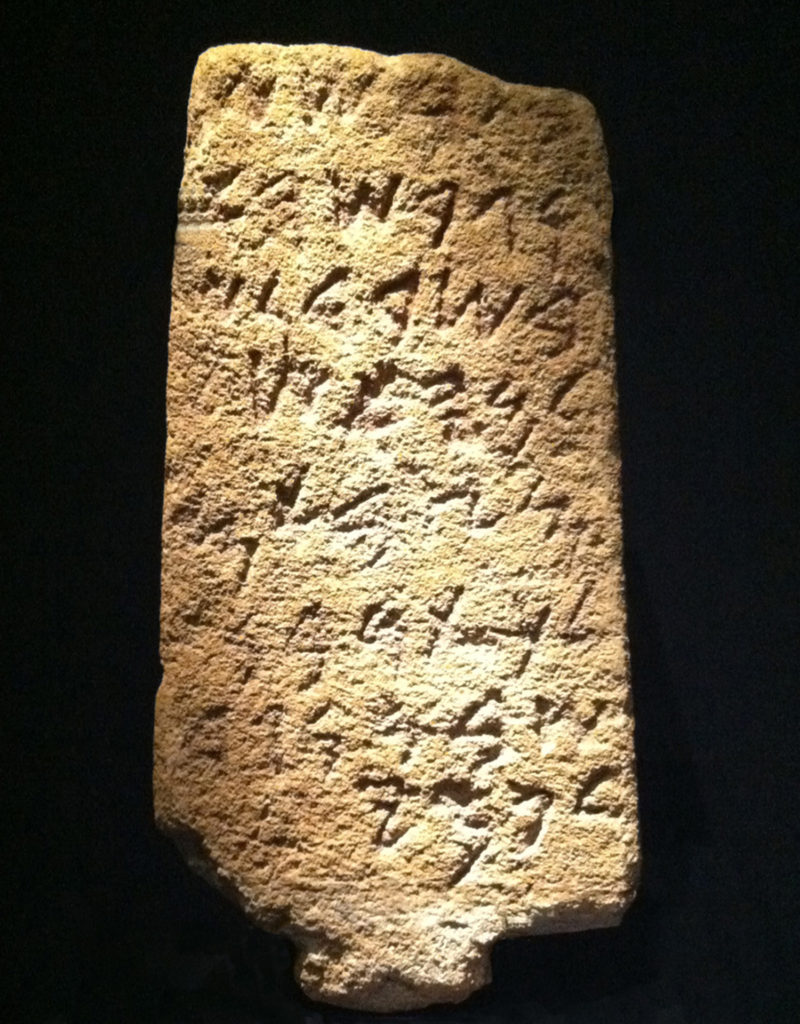

Rabbi Barbara told me that the Cagliari Jewish community, though not the largest in Sardinia, created an important center of Jewish life in the island’s capital. In the late 1990s, Rabbi Barbara’s friend, a Sardinian engineer named Giacomo Sandri, helped to discover an early medieval Jewish site in Cagliari. The site represented a complex world centered on the synagogue with a mikveh and a garden for a sukkah around it. The entire archaeological site was soon covered up to make way for new construction, and today, a garbage dump covers the ancient Jewish cemetery. Discovered artifacts were sent to the Cagliari Museum. However, when we visited the museum in September 2014, none were on display; instead, the Jewish artifacts were kept in storage for preservation. One artifact that I was interested in was shipped, as the curator on duty explained, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for their show “Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age.” It was the famous Nora Stone, the oldest existing example of the first alphabet, also called Proto-Canaanite or early Hebrew alphabet.

Little-known connections: the city of Nora and early Hebrews

Our next stop was the city of Nora situated on the south coast of Sardinia. Believed to be the first city founded in this island, Nora dates to the 11th century BC. This ancient city, most of which is said to be underwater, is of high interest to archaeologists. Nora was one of the most important centers of Phoenician expansion in the Mediterranean. Enterprising maritime traders, the Phoenicians were a Semitic people who spoke a language similar to Hebrew and were the first group to colonize both Sicily and Sardinia, attracted by Sardinia’s strategic location near important sea routes linking the Mediterranean with the Near East. The area was also rich with metal deposits, such as copper, iron, lead, and silver. The Phoenicians established their stronghold on the island; archaeological findings in Israel prove they imported silver during biblical times.

For me personally, Nora with its famous Nora Stone is placed forever at the roots of all recorded history and written literature of Western civilization. The Nora Stone, dating to the 9th century BC, was found at Nora in the late 1700s. The stone’s incised writing is considered to be the first alphabet. Unlike cuneiform script, one of the earliest known systems of writing that relied on multiple pictorial symbols, the Nora alphabet used less than thirty letters, one for each sound, and was written like Hebrew, from right to left. This Phoenician invention—alphabetic writing—spread across the world they colonized. By the first millennium BC, the people of the Levant, including the Phoenicians and Arameans, or Hebrews, were using a standardized alphabet, which was soon transformed to create other written languages such as Greek, Etruscan, and Latin. The very word “alphabet” comes from “aleph” and “bet,” the first two letters of the Phoenician writing system.

In Nora, not much is left from the Phoenicians. What visitors see today is mostly from the Roman period. The sunken city of Nora, as it is called, seems suspended between the sea and the sky, and walking through its ruins was almost a mythical experience. I could not help but think that, like the Phoenicians, who disappeared from history by being absorbed into much stronger civilizations of the Carthaginians and the Hebrews, the Jews of Sardinia were also pushed into historic oblivion, by forces of anti-Semitism and religious intolerance.

Jewish Sardinia today

Only a few Sardinian Jewish families returned to their ancestral island after the establishment of the unified state of Italy in the 1880s. Tragically, most of their descendants were killed during the Holocaust. Today there are very few Jews living in Sardinia, and there is no formal Jewish community on the island. However, just like in Sicily, an increasing number of people who suspect that they have Jewish roots are rediscovering these roots through the study of Judaism. Giacomo Sandri, an engineer from Cagliari, who assisted in discovering the ancient Jewish site there, wrote a book on Sardinian Jewish history and made an Orthodox-style conversion to Judaism. Since 1992, Rabbi Barbara has been officiating at conversions of the Sardinian Anousim, descendants of those who were forced to give up their Jewish identity over 500 years ago.

Today, Sardinia seeks to demonstrate the island’s resolve to remember its Jewish history and to preserve the evidence of Jewish civilization in Sardinia. On September 22, 2013, a square in Alghero was renamed Plaça de la Juharia(the Square of the Jews), recalling the fact that the square was once the center of the city’s Jewish quarter and the place where the main synagogue was located. This event, which was attended by hundreds of people, opened with the song “Avinu Malkeinu” performed by a local band. Taking part in the inauguration were Alghero’s mayor as well as the Israeli ambassador to Italy, who said: “This is a historic and symbolic gesture.” The mayor then delivered a speech and said that he would like to rectify the injustice caused to the town’s Jews in the past. He concluded by calling on Jews to return to Alghero. “Welcome home,” he said (Israel Jewish Scene, September 30, 2013).

The Anousim: what we learned from the “Children of the Forced Ones” in Sicily and Sardinia

In the contemporary European context of increasing anti-Semitic and anti-Israeli attitudes sometimes escalating to violence, Sicily and Sardinia present a new and unusually optimistic chapter in the history of the Jewish Diaspora. Our own journey in search of Jewish stories on these two islands brought our understanding of both Jewish history and Jewish identity to a new level.

The destruction of synagogues and the burning of “Judaizers” five centuries ago failed to extinguish the Jewish spirit. Rabbi Barbara told numerous stories, some from her own family, of traditions whose meaning was often forgotten but that survived in their homes’ secret cellars and in people’s hearts. Cooking continued to conform to kosher dietary laws. Family burials were done outside the church with bodies rapped in simple shrouds. Special marriage blessings were recited in a “strange language” at home under a crocheted canopy. Deathbed confessions of Jewish ancestry to the families were common. The Anousim descendants, whose heritage was so cruelly stolen, hidden, and ignored, sustained their history in their flesh and blood. And perhaps it is the call of blood that drives a continuously growing number of B’nei Anousimto search for their historical legacy and reclaim it.

Most Anousim have no records to prove their Jewishness, they just know that this is who they are. Traditional Judaism does not recognize their claim. It took over twenty years for Conservative Judaism to pass a resolution recognizing the Anousim and creating a welcoming space for those who want to return to the Jewish people. In the early 1990s, Rabbi Barbara Aiello, the first reform Rabbi in Italy, became a leader of the southern Italian B’nei Anousim movement. For over 25 years, Rabbi Barbara has been performing numerous conversions, Bar Mitzvahs, and weddings, and organizing educational events for Jews and non-Jews alike. In Sicily and Sardinia, a Jewish cultural and religious renaissance is on the rise, with events centered on Jewish history taking a prominent place in the intellectual environment of the south of Italy.

While working on my Sicilian-Sardinian study, I came across Steven Spielberg’s speech addressing the audience during the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of Auschwitz liberation. “If you are a Jew today,” said the founder of the Shoah Foundation, “you know that we’re once again facing the perennial demons of intolerance. Anti-Semites, radical extremists and religious fanatics that provoke hate crimes — these people want to, all over again, strip you of your past, of your story and of your identity … causing Jews to again leave Europe.” (World Jewry Digest, January 2015). It seems, I thought, that southern Italy and especially my beloved Sicily, prove to be different, once again trying to recreate the once and future world of acceptance and multiculturalism. Sheh Elohim Yevarech Othca—may this be blessed.

Read other little known stories of Jewish communities around the world in Irene Shaland’s book “The Dao of Being Jewish and Other Stories”

I did a dna test and thought I was 100% Sephardic, since all 4 of my grandparents came from turkey and told me I was Sephardic. The test came back stating i was 17% Sardinian, 27% Sephardic, 23% Ashkenazi, 14% Mizrahi, plus iberian pensinsularand italian dns . how can I find out my Sardinia roots.

Like a few others who have commented, I too am a Jew and have a small percentage of Sardinian DNA. I would love to visit Sardinia some day, seems like a very beautiful place.

Hello! I was wondering if there are any open synagogues in Sardinia? My boyfriend and I will be on the island for Rosh Hashana and wondering if there is anywhere where we can go to hear the shofar. Thank you and Shana Tova!!!!

Hi,

I am Jewish and I came with my friend last week to Sardinia from Munich for vacation.

I was looking for a Jewish community and I was surprised to hear that near-by Olbia there are no Jews. I checked the Internet and I was very happy to find this site.

I would like to contact Rabbi Barbara or any Jew in Sardinia.

I would appreciate very much if somebody could help me.

I speak German, English, Hebrew and my friend speaks Italian.

Knd regards and thank you very much in advance.

Charlotte Gavish

WhatsApp:

0049 172 5945474

Email:

charlotte.gavish@gmx.de

I just found my history via a DNA test indicates that I’v got 1% Sardinian in me. Both my parents are Jewish; Mom, Sephardic -Turkish and Dad from central Poland-Ashkenazic

Hi,

I have 100% Jewish DNA with 1% Sardinian. How may I learn more about my Sardinian roots? Is the book by Cagliari mentioned above available in an English translation?

Is there any listing of old family names of jewish descent in or from Sardinia?

Thanks,

Jerry

I did a gene test and to my surprise it seems my dads family came from Sardinia.I even have 2percent non Jewish genes.

Very informative. Beautiful photos.